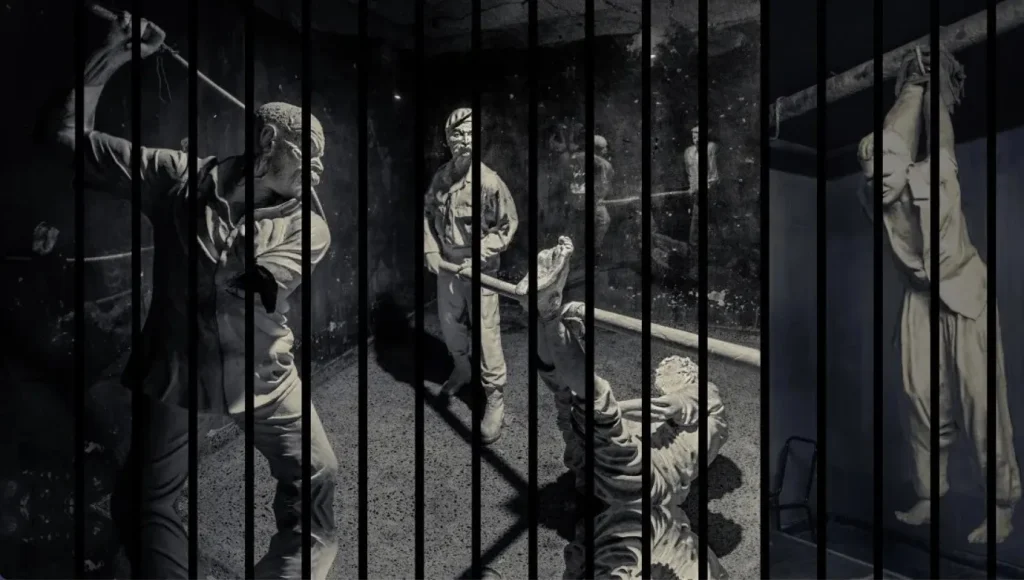

Image Source: Mahim Firaz Khan, CUSTODIAL TORTURE IN PAKISTAN (April 12, 2023,legalresearchandanalysis.com)

An Introduction to Custodial Torture

Pakistan’s formation and the years since have seen it attempt to grapple with one common thread of burden: introducing and implementing effective legislation. A stark gap between rules in theory and their application, as well as the complete absence of laws to govern specific areas remains an unresolved issue of primary significance.[1] Custodial torture is an area plagued by both these factors. The prevalent use of torture by law enforcement agencies in Pakistan is a fact that has long since been accepted by society and is often seen as a necessity for the furtherance of official activities.[2] To date, only sparse provisions relating to the prohibition of torture exist: scattered across the current Pakistani legal framework, they are vague, uncodified, and ineffective.

It wasn’t until the 1st of August that a government bill laid, known as the Torture and Custodial Death (Prevention and Punishment) Act 2021,[3] was passed by the National Assembly.[4] Yet to be taken up by Senate and therefrom to the President for assent, the passing of the bill is, nonetheless, a significant milestone in Pakistan’s commitment to human rights and its fulfilment of its international obligations. Its successful enactment (with some amendments) would mean that, for the first time in history, Pakistan would have a comprehensive statute specifically tackling torture, thereby removing conventional reliance upon inaccessible law prone to numerous hindrances.

Torture: The Legal Framework in Pakistan

The Constitution,[5] as the legal foundation of any country, is a prudent starting point. Article 9 of the Constitution stresses man’s right to life and liberty. Article 14(2) provides that anyone detained or in custody must be produced before a magistrate within a period of 24 hours of arrest. Similarly, Article 10A grants the right to a fair trial and due process. While these provisions do not explicitly recognise the prohibition of torture, they do, read together, provide vague boundaries that recognise the need to act fairly and transparently, in accordance with the law, when dealing with persons under custody. The only explicit mention of torture in the Constitution is found in Article 14. Stating that dignity of man is inviolable, the Article goes on to mandate that “no person shall be subjected to torture for the purpose of extracting evidence.”[6] On their own, these constitutional provisions offer little protection from torture. The only constitutional prohibition of torture is limited to the extraction of confessions and does not cover cases that may employ torture to punish, coerce, or intimidate. Seen merely as a legal foundation, however, upon which superstructure provisions are subsequently built upon in a bid to fill the gaps, the Constitution’s stance on torture, the dignity of man, and the need to act with due process within the boundaries of law sets up the groundworks for a framework adequately pitted against torture. However, such adequacy is of little use if the resulting laws on the matter are not comprehensive and effective.

The aforementioned resulting legislative provisions that deal with torture are largely found in the Pakistan Penal Code (the PPC)[7] and the Police Order 2002. The PPC criminalises acts of criminal force and assault,[8] wrongful restraint[9] and wrongful confinement,[10] acts that cause hurt with an intent to extort a confession,[11] as well as acts by public servants disobeying the law with the intent to cause injury to another person.[12] Whilst these provisions do successfully criminalise some acts that are ancillary to torture, it is imperative to recognise that they do not, of themselves, provide a comprehensive legal framework from a lens that caters to all forms of torture. The PPC does not explicitly mention or define torture; it only criminalises certain acts that may be considered to fall within a reasonable definition of the word (such as hurt, wrongful restraint, and wrongful imprisonment). Section 337-K of the PPC is essentially an extension of Article 14(2) of the Constitution and only criminalises acts of torture that cause hurt with the aim to extort a confession; any other hurt with an intent other than extorting a confession (such as punishing, coercing, and intimidating) are left with no recourse under this provision. Furthermore, the definition of hurt (battery and assault) for the purposes of Section 337-K in ss 350 and 351 of the PPC means that any mental suffering caused would not be seen as a criminal offence under Pakistan’s domestic framework.[13] Seen this way, Pakistan’s penal provisions merely overlap with some facets of torture but do not tackle the area in a comprehensive and effective manner. What remains is a disjointed area of law that is scattered, inaccessible for the layman, and prone to incompletely recognising all forms of torture.

Beyond the PPC, the Police Order 2002 penalises police offers who are found to have inflicted violence or torture upon any person in custody.[14] Whilst the statute prima facie presents a staunch answer to torture, there are many underlying caveats worth recognising. For one, the Order only applies to the extent of one province, Punjab, and not federally. Furthermore, the Order only applies to police officers, as opposed to all kinds of public officials who may use their office to torture (or implicitly allow such act) persons in custody. Perhaps most glaringly, the Order does not define what constitutes torture for its purposes. This is also the case for the PPC and the Constitution.

The Prevalence of Torture

In the absence of a comprehensive domestic framework, it is perhaps no surprise to find that little oversight exists in curbing torture and that its prevalence remains pervasive as a tool employed by law enforcement agencies acting with impunity. A legal framework operating without an explicit definition of torture has no way of effectively demarcating acts that constitute torture: curbing its prevalence is an altogether different task.

Acts of torture employed by the officials include the likes of beating and suspending those in custody.[15] A study carried out by Justice Project Pakistan and the Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic[16] investigated allegations of abuse in Faisalabad (a major city in Pakistan). It reported that of 1,867 Medico-Legal Certificates (MLCs) assessed, around 76 percent of the cases were found to have “conclusive signs of abuse” with an additional 5 percent of cases indicating signs of injury but which required further testing to confirm.[17] The physicians involved in the assessments found that the police had beaten, suspended, stretched, and crushed victims and that, in some cases, solitary confinement, sleep and sensory deprivation, and sexual abuse was seen.[18] Abuse in custody, however, was likely to be more widespread than the report suggested: the 1,867 cases assessed included only those people who were willing to come forward and complain against the police, as opposed to those who shirked away in fear of retaliation; practical barriers also contribute significantly to the absence of accountability and the resulting impunity.

The existence of such affairs, in addition to the practical and legal problems discussed above, is also exacerbated by other barriers. Police departments operate with little oversight. To date, Pakistan does not have an independent state-sponsored institution designated to oversee allegations of torture.[19] Instead, such cases are investigated by law enforcement agencies. In a framework that clearly showcases bias and partiality, the reporting and subsequent investigation of cases involving torture allegations are conducted by police officials,[20] who are prone to causing delays and act uncooperatively.[21]

The recent case of Salahuddin Ayyubi and its viral footage evidencing police brutality on a mentally challenged man in custody, who then succumbed to fatal injuries inflicted, is an indicative example.[22] The likes of Amir Masih[23] and Malik Waqqar Ahmad[24] comprise but a few names of the many affected by custodial torture.

International obligations

In addition to ratifying the seminal International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights which prohibits torture and ill-treatment, Pakistan also became a signatory to the United Nation’s United Nations Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT)[25] in 2008. Ratifying the latter in 2010, the years since have seen Pakistan show wavering resolve in meeting its binding international obligations.

Beyond submitting its initial state report four years late and therein audaciously claiming that the piecemeal and scattered legal provisions on torture provided an adequately comprehensive legal framework,[26] Pakistan is still (until the pending Bills on the matter are passed, at least) in breach of Article 4 of the Treaty which states that all acts of torture, as defined, are made criminal offences under States’ criminal law. Bills tabled by various member of Parliament on the matter over the year subsequent to ratification have all been allowed to lapse.[27] The recent government bill passed by the National Assembly, however, may prove to be the one that crosses the finishing line.

The Torture and Custodial Death (Prevention and Punishment) Act 2021[28]

The recent passing of the government Bill is a welcome act; for the first time in Pakistan’s history, the National Assembly has passed legislation that criminalises torture in a comprehensive manner.[29] The Bill broadly defines custody[30] to include any instance of detention or deprivation of liberty by a public official, including cases of judicial remand as well as search, arrest, and seizure proceedings. Sections 2(h) and (i) of the Bill define custodial death and rape broadly with indirectly imputable death being an offence under the former as well. The Bill demarcates and prescribes separate penalties for both in ss 9 and 10. Furthermore, Section 3 of the Bill reaffirms Article 15 of CAT by expressly stating that statements obtained as a result of torture are inadmissible as evidence. Section 14 of the Bill allows a complainant to move a special protection petition before the Sessions Court in fulfilment of Article 15 of CAT, whereas Section 18 mandates public awareness of the Bill’s provisions and periodical public officials’ sensitisation to torture. These provisions ensure the Bill’s long-term commitment to a torture-free Pakistan that prioritises the safety of those who speak up and actively pursues the proper training of personnel.

Despite these commendable provisions, there remains scope for improvement. Many pursuable reforms can be found in a parallel private bill on custodial torture originating (and subsequently passed) in Senate.[31] For one, the government bill passed by the NA defines torture narrowly and in contravention of CAT; it only includes in its remit those acts which cause “physical pain or physical suffering”.[32] The Private Bill, however, includes in its counterpart definition mental pain and suffering as well. Amending the government bill to include mental hurt as a kind of torture would allow align Pakistan with its international obligations as a signatory to CAT and allow countless people who have been subjected to such torture some recourse. Furthermore, the government bill links punishment of various offences under the Bill to the PPC. This is confusing and a further source of overlapping within the current framework. A more prudent way forward would be the one adopted by the private Bill: to explicitly set out in the specific law itself the punishment for specific crimes.[33] Amongst the few absences in the Government Bill is the complete overlooking of the need to provide redress to the complainant (as mandated by Article 14 of CAT). While the bill prescribes punishment, there is no mention of any redress or compensation to the complainant. On the other hand, the Private Bill comprehensively stresses that all fines recovered by way of punishment be paid to the victim or, in the case of custodial death, to the heirs of the legal victims. Amending the Government Bill to incorporate such a practical provision would mean that the victims and all their beneficiaries are compensated tangibly for hurt caused, beyond any sentence awarded to the perpetrator.

Perhaps the chief shortfall in the Government Bill, however, is its granting of exclusive investigative authority of complaints to the Federal Investigating Agency (FIA) under Section 5. As a part of the Police Establishment, and a division that has been prone to calls of bias,[34] the FIA being handed such a task is a colossal conflict of interest. The Private Bill provides a feasible middle-ground by granting the FIA “primary jurisdiction to investigate the complaints… until such time as the Commission [National Commission for Human Rights] is functional with an investigative infrastructure…”[35] Harbouring the intent to assign such tasks in the long-run to the Commission would be a sturdy step towards establishing an impartial unit that would investigate without any fingers being raised regarding departmental loyalties.

Conclusion

The recent Government Bill, having received the requisite number of votes from the Lower House, is likely to now become a law (contingent upon Presidential Assent). Being a fairly comprehensive bill, it does, nonetheless, have its shortfalls. The Senate would do well to highlight the concerns and lacunae in it for the National Assembly to then take up and forward. Enacting such legislation would is a necessity and would be a big milestone. Yet, there remains much to be done. The legislation must be made functional and implemented in spirit to overcome years of the systemic use of torture that has been accepted by governments and socio-culturally.

[1] By way of example, domestic violence is an area that remains heavily controversial and attempts thus far to introduce federal legislation on the matter remain unsuccessful.

[2] Justice Project Pakistan, ‘Criminalising Torture in Pakistan: The Need for an Effective Legal Framework’, (Justice Project Pakistan n.d) 4.

<https://www.omct.org/site-resources/images/Pakistan-report.pdf> accessed 8 August 2022.

[3] The Torture and Custodial Death (Prevention and Punishment) Act 2021.

<https://na.gov.pk/uploads/documents/1632982253_871.pdf> accessed 6 August 2022.

[4] Syed Irfan Raza, ‘NA bill suggests capital punishment for officials over deaths in custody’ Dawn (2 August 2022) <https://www.dawn.com/news/1702812> accessed 3 August 2022.

[5] The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan 1973.

[6] Ibid, Article 14(2).

[7] Pakistan Penal Code 1860.

[8] Ibid, ss 350-358.

[9] Ibid, Section 339.

[10] Ibid, Section 340. Section 349 specifically deals with wrongful confinement with the intent to extort a confession regarding a crime or misconduct, or to restore property.

[11] Section 337-K (n 7).

[12] Section 166 (n 7).

[13] Hurt is defined in both sections as the use of force (battery) or any gesture causing the apprehension of use of force (assault). Only such hurt qualifies for the purposes of Section 337-K.

[14] Section 156(d), The Police Order 2002.

[15] Policing as Torture: A Report on Systematic Brutality and Torture by the Police in Faisalabad, Pakistan (p 7). Justice Project Pakistan and Allard K. Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic. March 2014. https://www.jpp.org.pk/report/policing-as-torture.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid, 6.

[18] Ibid, 7.

[19] Ibid, 37. Whilst the Private Bill laid by Senator Sherry Rehman (considered below) offers the National Commission for Human Rights a secondary role in the investigations of such allegations, the Government Bill recently passed by the National Assembly leaves the remit of such activities to the Federal Investigation Agency.

[20] ‘Criminalising Torture in Pakistan: The Need for an Effective Legal Framework’ (n 2), 2.

[21] Ibid, 39.

[22] Xari Jalil ‘Turning a Blind Eye to Torture’ Dawn (7 August 2022) <https://www.dawn.com/news/1703708> accessed 8 August 2022.

[23] Web Desk , ‘CCTV Video of Amir Masih lends credence to torture claims’ The News (8 September 2019) <https://www.thenews.com.pk/latest/523952-cctv-video-of-amir-masih-lends-credence-to-torture-claims> accessed 9 August 2022.

[24] Sarah Belal ‘End the Impunity’ The News (2 June 2018) <https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/324372-end-the-impunity> accessed 9 August 2022.

[25] Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

International Covenant for Civil and Political Rights (adopted 10 December 1984, entered into force 26 June 1987) 1465 UNTS 85 (CAT).

[26] The Government of Pakistan ‘Pakistan’s Initial Report On United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman Or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), para 4.

<https://mohr.gov.pk/SiteImage/Misc/files/CAT.pdf> accessed 6 August 2022.

[27] ‘Criminalising Torture in Pakistan: The Need for an Effective Legal Framework’ (n 2), 5.

[28] Torture and Custodial Death Bill 2021 (n 3).

[29] Having originated in the NA, the Bill has, at the time or writing, been sent to the Senate. Upon approval from the latter and subsequent assent by the President, as well as the taking up the NA of any amendments the Senate may suggest, the Bill will become law.

[30] Section 2(n), (n 3).

[31] The Torture and Custodial Death (Prevention and Punishment) Bill 2021 <https://senate.gov.pk/uploads/documents/1626179451_937.pdf> Accessed 9 August 2022.

This alludes to the Private Bill laid by Senator Sherry Rehman and not the Government Bill passed by the National Assembly discussed thus far.

[32] Section 2(n), (n 3).

[33] For example, Section 3 of the Private Bill provides imprisonment for a minimum of three-years and up to ten years, as well as a fine. On the contrary, Section 8 of the Government Bill links the punishment of torture rather vaguely to “the same punishment as prescribed for the type of harm provided in Chapter XVI of the Pakistan Penal Code.”

[34] Justice Project Pakistan ‘Live with JPP Episode 8: Criminalizing Torture – Triumphs and Road Ahead’ (5 August 2022) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BpnJG8CL9BQ> accessed 9 August 2022. See also note 22.

[35] Section 10 (n 30).

Bibliography

Pakistani Legislation

Pakistan Penal Code (Act XLV of 1860).

The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan 1973.

The Police Order 2002 (C.E. Order No.22 of 2002).

The Torture and Custodial Death (Prevention and Punishment) Act 2021.

Treaties

Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (adopted 10 December 1984, entered into force 26 June 1987) 1465 UNTS 85

International Covenant for Civil and Political Rights (adopted 16 December 1966, entry into force 23 March 1976) 999 UNTS 171.

Secondary Sources

Belal S, ‘End the Impunity’ (The News, 2 June 2018).

Jalil X, ‘Turning a Blind Eye to Torture’ (Dawn, 7 August 2022).

Justice Project Pakistan and Allard K. Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic, ‘Policing as Torture: A Report on Systematic Brutality and Torture by the Police in Faisalabad, Pakistan’ (March 2014).

Justice Project Pakistan, ‘Criminalising Torture in Pakistan: The Need for an Effective Legal Framework’, (Justice Project Pakistan, n.d).

Justice Project Pakistan ‘Live with JPP Episode 8: Criminalizing Torture – Triumphs and Road Ahead’ (YouTube, 5 August 2022).

Raza S.I, ‘NA bill suggests capital punishment for officials over deaths in custody’ (Dawn, 2 August 2022).

The News, ‘CCTV Video of Amir Masih lends credence to torture claims’ (The News, 8 September 2019).

Authors

Smam Mir, Team Lead and Coordinator RCIL&HR (smamabdallah10@gmail.com)

Momina Moin, Research Assistant RCIL & HR (momeenamoin@gmail.com)