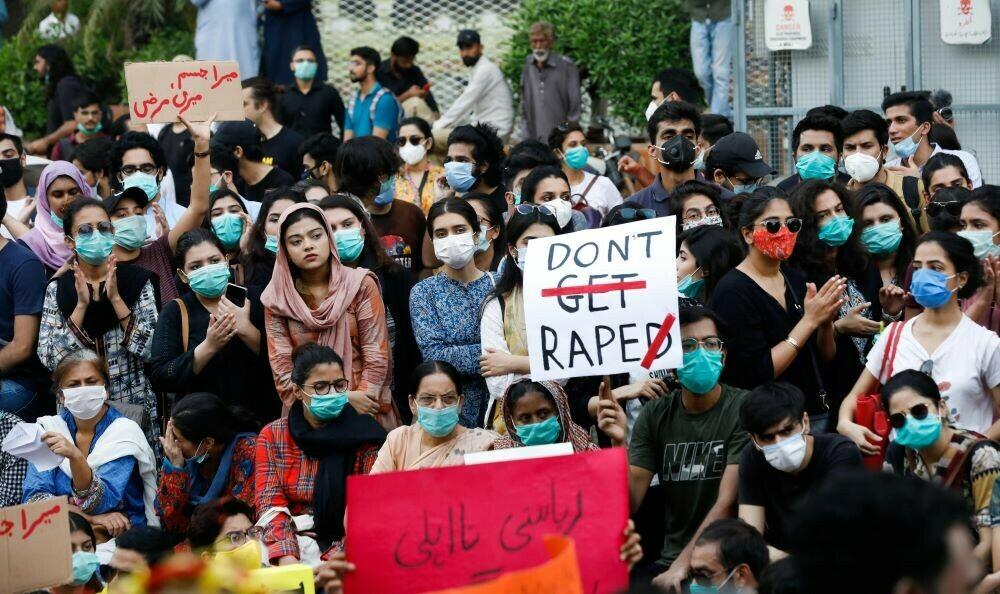

Image Source: Shaping justice — tracing the evolution of rape laws in Pakistan – Pakistan – DAWN.COM

Pakistan has been struggling with the problem of sexual misconduct throughout history. The criminalization of the conduct of sexual assault (SA) was introduced by the Pakistan Penal Code (Act XLV of 1860).[1] However, this action did not lead to improvement of the situation in the society as the Act was limited in scope, and there was a lack of will to properly implement such Act.[2] One of the most controversial points within the Act is that it was assumed that the practice of rape is solely conducted by a male against a woman.[3] Such limitation completely disregards the disappointing reality of SA against male children, transgender community, as well as other men. Furthermore, by classifying “rape” solely as “sexual intercourse”, the Act completely overlooks all other types of SA that do not necessarily constitute penetration.[4]

Additionally, it is important to discuss the social stigma around the topic, and the gender inequality in the Pakistani society, which significantly impacted the implementation of such Act. The official police reports would lack information; forensic data would be disregarded. Such misconducts can be assigned to the predominantly male judicial system that would show more compassion towards the male perpetrators by “spinning” the evidence in their favor, while women would be advised not to admit to being sexually assaulted as they would be judged, and rejected, by the local society.[5]

It can be seen that there was not much effort to promote change and a fairer legal system. This was not the case, until the decision in Salman Akram Raja and Tahira Abdullah v Government of Punjab[6] case in 2013 that led to a surprisingly positive judgment of the Supreme Court of Pakistan. It was ruled that police stations were to initiate partnerships with civil society organizations that would provide counseling of any kind; DNA testing was to be made mandatory in investigations; “protection programs” were to be developed that would allow the victim to pre-record a statement and avoid meeting the perpetrator in the courtroom.

After this ruling, it was estimated that around 11 SA cases were reported on a daily basis from 2015 up until 2020, which amounts to over 22,000 reported cases in this time period. However, the most saddening fact is that out of 22,000 cases, only 77 have been resolved by sentencing the perpetrators.[7]

The ultimate “steppingstone” that led change in the Act were the two highly media publicized instances of rape in 2018 and 2020, respectively. The former involved the kidnapping and a sexual assault of a 7-year-old girl, Zainab Amin Ansari. The latter case shed light on “gang-rape”, where multiple offenders assaulted a woman on the Lahore-Sialkot motorway. Both cases resulted in major backlash of the Pakistani government by the civil society.[8]

Therefore, in December 2020, Criminal Law (Amendment) Ordinance[9] and the Anti-Rape (Investigation and Trial) Ordinance[10] (ITO 2020) were passed to address the shortcomings of the previous Act. On the positive side, the Amendment led to the broadening of crucial notions as it became gender neutral as parties are now categorized as Person A/B, no longer assigning genders to the roles of offender/victim. Additionally, the notion of “Gang Rape” was added in order to be able to prosecute all the perpetrators involved on the same legal basis. Furthermore, the previous definition of rape as solely an act of penetration, is now expanded to include every sexual act that does not operate under the consent of both parties, and is considered as a non-compoundable offence.[11]

Nevertheless, the Amendments do not bring about much practical change. From October 2020 until October 2021, there was over 1,000 reported SA cases of women/men, children, and transgender people.[12] Such a situation is a result of a weak governmental system that relies on underfunded police force and underdeveloped judicial system, as seen through the case of Yasir v The State & another.[13] The focal point of the ruling made by Lahore High Court is that the proliferation of SA cases continues because Section 9 of ITO 2020 which calls for the creation of Joint Investigation Teams and the appointment of certain investigation officers has been fully disregarded. This neglect allows for SA cases to not be given the attention that they deserve and offenders walking away freely. Furthermore, chemical castration as a new punishment gathered a lot of criticism, but this point will be discussed in detail further on in the blog.

Comparative Analysis

For a concise analysis, the newly reformed anti-rape laws of Pakistan would be compared with those of Bangladesh, India, and Nepal, which have comparable legal systems. The ultimate aim is to conclude that the current laws in Pakistan are more responsive to the needs of the victims than those in the three countries in the following aspects.

a. Gender

Pakistan appears to be the only gender-neutral state in terms of the extent of its anti-rape laws among these four countries. Rape can be committed by either a male, female, or transgender.[14] Given that the scope of gender in Bangladesh, India, and Nepal is confined to male and female, this is undeniably a step forward in legal development.[15] Interestingly, the language in Nepal is even more detailed, since it covers the alternative scenario of a male having sexual intercourse with a girl child under the age of eighteen, so excluding a situation in which a boy child is raped.[16] Therefore, not limiting itself to the traditional understanding of gender, Pakistan provides a progressive and inclusive legal framework that protects transgender people as well.

b. Penetration

Rape is defined in Bangladesh as solely peno-vaginal penetration.[17] Other types of sexual penetration are classified as “unnatural offences” or “sexual oppression” and “assault,” with significantly lower penalties.[18] Likewise, rape in Nepal does not encompass all acts of sexual penetration, i.e. the concept of rape includes only penetration of the vagina and not penetration of other bodily orifices.[19] In this regard, the Indian and Pakistani definitions of rape are identical, in that they both encompass all acts of sexual penetration as well as oral sex (without a requirement for penetration).[20] Rape is considered as an offense against the chastity and honour of the woman when the definition of rape is limited to peno-vaginal penetration, while stressing procreative sexual actions.[21] Laws that focus on violations of honor rather than coercion deprive the victim of justice.[22] They establish a hierarchy of “worthy” survivors, promote the image of women as carriers of a society’s “morality”, and develop an atmosphere in which women’s bodies and lives are controlled and the guilt for sexual assault is placed on the victim.[23] Accordingly, Pakistan is and should continue to criminalize all acts of sexual penetration in order to effectively eradicate the rape endemic.

c. Circumstances

In India and Pakistan, the Penal Codes list seven scenarios under which a person can commit rape.[24] In Bangladesh, these circumstances are more limited, due to the problematic requirement of consent. First, in the case of adult victims, Bangladeshi law does not deal with the issue of incapacity to provide consent at all, including unsoundness of mind, intoxication or unconsciousness.[25] Second, rape is considered to be committed with or without the victim’s consent if she is under the age of fourteen.[26] Consequently, Bangladeshi laws have a lower age limit than Pakistani laws, which demand sixteen years of age. However, it is unclear from the language what happens to victim minors aged fourteen and above. As a result, Bangladesh could adopt Pakistan’s good practices to achieve justice.

d. Marital rape

Marital rape laws convey a larger message to the world that women are subordinate to their husbands and sow the seeds of legal and cultural discrimination, thereby giving women second-tier status with no individual autonomy.[27] The UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women proposes that criminal laws be changed or new criminal provisions be enacted to outlaw marital rape.[28] Both India and Bangladesh appear to be in violation of international standards since the law permits marital rape. In Bangladesh it is the rape of adult women in all circumstances, whereas in India, unless the parties are separated.[29] Because there is no explicit section on marital rape in Pakistan, it is ambiguous and uncertain whether marital rape is criminalized or not.[30] Hence, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India should follow Nepal’s lead in criminalizing marital rape.[31]

The Morality of Chemical Castration

One of the largest areas of contention in relation to the two newly established ordinances is the use of chemical castration as a form of punishment. The use of chemical castration is very clearly not a form of torture, however the inhumanity and ignominy of it is subject to debate within Pakistan. Pakistan’s constitution is very clear about every man’s right to be treated with dignity on the basic human level. Section II of the constitution, the part establishing the fundamental rights of Pakistani citizens, states, “The dignity of man and, subject to law, the privacy of home, shall be inviolable”.[32] The argument now is: despite the sheer atrociousness and vile nature of rape, is it ultimately constitutional to subject those found guilty of rape/gang rape in extreme situations to chemical castration.

The use and extent of chemical castration as a form of punishment varies from nation to nation. In Australia there is a law permitting the use of chemical castration, however only if the offender volunteers to undergo this treatment. Australian laws concerning chemical castration are clear in this regard.[33] To some this is still seen as not enough; it should not be up to the offender to make this decision. Chemical castration and prison time could be seen as an ideal combination between immediate punishment and longer lasting effects to prevent another future crime. Across the ocean rules are different from both Australia and Pakistan. In the United States there are certain states that have chemical castration as a part of compulsory medical treatment in response to a sexual offender.[34] Aside from the legality of utilizing chemical castration, there are also increasing questions from those in the medical world as to whether castration, chemical or physical, is really the solution to stopping offenders potentially repeating. There have been some studies illustrating the long-term effects, such as reduced bone strength, osteoporosis, and depression according to the Journal of Korean Medical Science.[35] Those who support a more standardized use of chemical castration point to there being a greater social benefit as well as punishment for the offender. In this view if an offender is released back into society, after undergoing chemical castration, they pose less of a threat to reoffend and to society. Supporters of this format of punishment look towards ever increasing numbers of inmates in prison and see chemical castration as a means to also help rehabilitate the offender so they can potentially be released back into public.[36]

Conclusion

With the creation of these two ordinances in Pakistan’s constitution there will be continued debate over chemical castration and the battle between ethical vs legal. In the future more clarity will be needed within Pakistani law, however there is no doubting that the ordinances are a step in the right direction and could lead to future debates in other areas stemming from the ordinances. While the use of chemical castration is a genuine discussion that should be had, it will be important to not forget that ultimately the goal is to reduce the prevalence of rape in Pakistan, and to appropriately hold accountable those found guilty of such acts.

Finally, in regard to the efforts to decrease the number of SA cases in Pakistan, the theoretical base exists, but there is no firm implementation of the new ordinances. The rates of rape are still high in Pakistan, and without a real implementation of the ordinance legislation, a true difference cannot be made. For Pakistan to move forward and witness genuine change the government will need to step up to the plate. The victims of rape deserve to be given all the resources promised and are entitled to be treated with respect, fairness, and the most secure process of law. This will entail establishing the investigation teams across the country, gathering necessary resources, strengthening the police force, and forming a more efficient judicial system.

But, let us not forget the main issue that needs to be addressed – the lack of actual will to protect Pakistani women and children. The new Ordinances are not a product of common sense, but rather a result of ad-hoc populism. Had there been no media backlash, the Pakistan Penal Code would have remained the way it was. At this point, such situation can only be addressed by allowing the unimpeded inclusion of women in all spheres of life. Only then would their voices be heard in the decision making, and that would lead to the earnest arguing towards “female-friendly” laws on the sole basis that women deserve equal rights.

[1] Pakistan Penal Code (Act XLV of 1860).

[2] ibid.

[3] ibid.

[4] ibid.

[5] Maliha Zia Lari, ‘Rape Laws in Pakistan: A History of Injustice’ (Dawn, 30 March 2014) <https://www.dawn.com/news/1096629> accessed 29 March 2022.

[6] [2013] SCMR 203.

[7] Web Desk, ‘11 Rape Incidents Reported in Pakistan Every Day, Official Statistics Reveal’ (The News, 13 November 2020) <https://www.thenews.com.pk/latest/743328-about-11-rape-cases-reported-in-pakistan-every-day-official-statistics-reveal> acessed 29 March 2022.

[8] Isha Shahid Bilal, ‘Reform of Rape Law in Pakistan: A Temporary Fix or New Beginnings?’ [2021] 5(1) PCL Student Journal of Law, 6.

[9] Criminal Law (Amendment) Ordinance, 2020.

[10] Anti-Rape (Investigation and Trial) Ordinance, 2020.

[11] Meaning: No settlement is allowed between the parties, and the Court has to give the final judgment.

[12] Sajjal Jamil, ‘Data: One Year of Rape Cases in Pakistan’ (The Current, 12 October 2021) <https://thecurrent.pk/data-one-year-of-rape-cases-in-pakistan/> acessed 29 March 2022

[13] Yasir v The State & another Crl. Misc. No. 43708-B/2021 [9].

[14] Criminal Law (Amendment) Ordinance, 2020 (Pakistan), s 375 explanation 3.

[15] Penal Code for Bangladesh, 1860 ACT NO. 45 OF 1860, s 8; Indian Penal Code, 1860 ACT NO. 45 OF 1860, s 8; The National Penal (Code) Act, 2017 ACT NO. 36 OF 2017 (Nepal), s 219.

[16] National Penal Code (Nepal) (n 13) s 219 sub-s 2.

[17] Penal Code for Bangladesh (n 13), s 375.

[18] Ibid s 377.

[19] National Penal Code (Nepal) (n 13) s 219.

[20] Ordinance, 2020 (Pakistan) (n 12), s 375; Indian Penal Code, 1860 (n 13) s 375.

[21] Sexual Violence in South Asia: Legal and Other Barriers to Justice for Survivors (Equality Now and DAI, 2021) 19 <https://www.equalitynow.org/resource/sexualviolencesouthasia/> accessed 29 March 2022.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ordinance, 2020 (Pakistan) (n 12): (i) Against B’s will; (ii) Without B’s consent; (iii) with B’s consent, which has been obtained by putting B or any person in whom B is interested, in fear of death or of hurt; (iv) with B’s consent, when A knows that A is not B’s husband and that B’s consent is given because B believes that A is another man to whom B is or believes herself to be lawfully married; (v) with B’s consent when, at the time of giving such consent, by reason of unsoundness of mind or intoxication or the administration by A personally or through another of any stupefying or unwholesome substance, B is unable to understand the nature and consequences of that to which B gives consent; (vi) With or without B’s consent, when B is under sixteen years of age; (vii) When B is unable to communicate consent. (The wording in the Indian Penal Code (n 2) is identical, as within its context A is worded as man and B is the woman.)

[25] See Indian Penal Code (n 13) s 375.

[26] Penal Code for Bangladesh (n 13), s 375.

[27] Sexual Violence in South Asia (n 19) 24.

[28] United Nations Women, Handbook for Legislation on Violence against Women (2012) <https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2012/12/handbook-for-legislation-on-violence-against-women> accessed 29 March 2022, 4; See also UNHRC ‘Report of Dubravka Šimonović – Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, on her mission to the Bahamas’ (25 May 2018) UN Doc A/ HRC/38/47/Add.2, para 73(h).

[29] Penal Code for Bangladesh (n 13), s 375, see Exception; Indian Penal Code (n 13) s 375, see Exception 2.

[30] Ordinance, 2020 (Pakistan) (n 12), s 375: The law states unequivocally that the woman against whom the rape is being committed can be any woman. However, it does not clarify whether that is applicable in the spouse relationship.

[31] National Penal Code (Nepal) (n 13) s 219 sub-s 4.

[32] The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973.

[33] Pugh, Jonathan. “The Ethics of Compulsory Chemical Castration: Is Non-Consensual Treatment Ever Permissible?” Practical Ethics, http://blog.practicalethics.ox.ac.uk/2015/08/the-ethics-of-compulsory-chemical-castration-is-non-consensual-treatment-ever-permissible/.

[34] Grubin, Don, and Anthony Beech. “Chemical Castration for Sex Offenders.” BMJ: British Medical Journal, vol. 340, no. 7744, BMJ, 2010, pp. 433–34, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25674107.

[35] Lee, Joo Yong, and Kang Su Cho. “Chemical Castration for Sexual Offenders: Physicians’ Views.” Journal of Korean Medical Science, The Korean Academy of Medical Sciences, Feb. 2013, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3565125/#:~:text=Therefore%2C%20chemical%20castration%20is%20associated,and%20anemia%20can%20also%20occur.

[36] Grubin, Don, and Anthony Beech. “Chemical Castration for Sex Offenders.” BMJ: British Medical Journal, vol. 340, no. 7744, BMJ, 2010, pp. 433–34, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25674107.

Bibliography

Pakistani Cases

Salman Akram Raja and Tahira Abdullah v Government of Punjab [2013] SCMR 203

Yasir v The State & another Crl. Misc. No. 43708-B/2021 [9]

Pakistani Legislation

Anti-Rape (Investigation and Trial) Ordinance 2022

The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973

Criminal Law (Amendment) Ordinance 2022

Pakistan Penal Code (Act XLV of 1860)

Foreign Legislation

Penal Code for Bangladesh, 1860 ACT NO. 45 OF 1860, s 8; Indian Penal Code, 1860 ACT NO. 45 OF 1860, s 8; The National Penal (Code) Act, 2017 ACT NO. 36 OF 2017 (Nepal), s 219.

Secondary Sources

Grubin, Don, and Anthony Beech. “Chemical Castration for Sex Offenders.” BMJ: British Medical Journal, vol. 340, no. 7744, BMJ, 2010, pp. 433–34, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25674107

Isha Shahid Bilal, ‘Reform of Rape Law in Pakistan: A Temporary Fix or New Beginnings?’ [2021] 5(1) PCL Student Journal of Law, 6

Lee, Joo Yong, and Kang Su Cho. “Chemical Castration for Sexual Offenders: Physicians’ Views.” Journal of Korean Medical Science, The Korean Academy of Medical Sciences, Feb. 2013, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3565125/#:~:text=Therefore%2C%20chemical%20castration%20is%20associated,and%20anemia%20can%20also%20occur

Maliha Zia Lari, ‘Rape Laws in Pakistan: A History of Injustice’ (Dawn, 30 March 2014) <https://www.dawn.com/news/1096629> accessed 29 March 2022

Pugh, Jonathan. “The Ethics of Compulsory Chemical Castration: Is Non-Consensual Treatment Ever Permissible?” Practical Ethics, http://blog.practicalethics.ox.ac.uk/2015/08/the-ethics-of-compulsory-chemical-castration-is-non-consensual-treatment-ever-permissible/

Sajjal Jamil, ‘Data: One Year of Rape Cases in Pakistan’ (The Current, 12 October 2021) <https://thecurrent.pk/data-one-year-of-rape-cases-in-pakistan/> acessed 29 March 2022

Sexual Violence in South Asia: Legal and Other Barriers to Justice for Survivors (Equality Now and DAI, 2021) 19 <https://www.equalitynow.org/resource/sexualviolencesouthasia/> accessed 29 March 2022

United Nations Women, Handbook for Legislation on Violence against Women (2012) <https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2012/12/handbook-for-legislation-on-violence-against-women> accessed 29 March 2022, 4; See also UNHRC ‘Report of Dubravka Šimonović – Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, on her mission to the Bahamas’ (25 May 2018) UN Doc A/ HRC/38/47/Add.2, para 73(h)

Web Desk, ‘11 Rape Incidents Reported in Pakistan Every Day, Official Statistics Reveal’ (The News, 13 November 2020) <https://www.thenews.com.pk/latest/743328-about-11-rape-cases-reported-in-pakistan-every-day-official-statistics-reveal> acessed 29 March 2022

Authors

Amina Zekovic, Research Assistant, RCIL & HR

Caleb Stangl, Research Assistant, RCIL & HR

Firdes Shevket, Research Assistant, RCIL & HR